This blog post is a quick overview of some of the ongoing issues to studying acupuncture in western-style clinical trials. If the idea of this bores you, skip to the final paragraphs for a short summary.

Clinical studies for acupuncture in the West have generally been undertaken by well-meaning researchers, most of them competent. As you may know, western clinical research has an abiding kink for Descartes, the famous European theorist who implored us to break all things down into their constituent parts and then study the parts to understand the whole. This approach has proven problematic for acupuncture research because acupuncture is embedded in Asian medicine and theory, which views things as inter-dependent and therefore inextricably connected by their nature.

In their article What is the Point? Drs. Langevin and Wayne discuss current problems in acupuncture research, and argue primarily that “as a first step, it is essential to “clean up” the assumptions and language used in acupuncture research…”. Importantly, they promote the idea that location of acupuncture points should be described with Western anatomy and physiology.

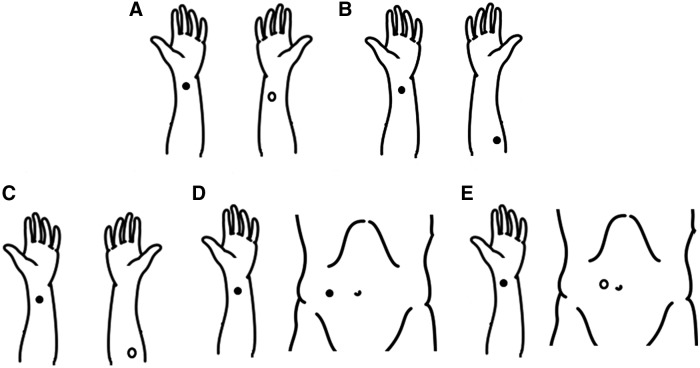

What’s the issue with that? The issue is that acupuncture points are often located by palpation (touch) and the location can be adjacent to a textbook anatomical location, due to the variation in patient’s body structure and tissue distribution. So when, in a study, an acupuncture point is identified as “PC6”, it means where the point is both palpably and anatomically, and not divorcing the two.

The idea of “sham acupuncture” was developed for clinical trials to create controls, including methods that create the illusion of receiving acupuncture or needle insertion at a defined, ‘non-acupuncture point’ location on the body. Sham acupuncture has not been successful, overall. First, according to Asian Medicine classic texts, there is no point on the body that can’t be used as an acupuncture point. Second, methods of sham acupuncture have been rudimentary until very recently. It’s tough to fool someone that a needle was(n’t) inserted into their body!

Also, there exists a vast swath of good data from Asia. The most robust (and always discounted) form of this data is recorded in the tradition, in the wealth of the texts in Asian Medicine. Each of these texts, spanning 2200 years, meticulously builds on the previous, evolving and refining the theory and treatment protocols based on clinical experience. It is likely the most robust record of medical practice that is directly applicable to this day.

Additionally, there is a wealth of good, western-style clinical studies on acupuncture and Asian medical practices (esp. herbology) that requires fluency or access from Mandarin, Japanese, or Korean. A deep bow to Doctoral students and researchers and dedicated practitioners like Heineur Fruehauf, who dedicate themselves to research and clinical work in Asia.

So, in sum, the issue doesn’t appear to be acupunctures’ efficacy in practice. The main issue with studying acupuncture in western clinical trials is the Descartian method of isolating the method of acupuncture, and then asserting it exist in western anatomical and physiological contexts.

For millennia acupuncture has been used as a method within Asian medicine, rather than an isolated medical procedure. It’s akin to a Doctor of Osteopathy using manual adjustments: The treatment method stems from the diagnosis, and acupuncture is always embedded within a wider framework of Asian medical theory.